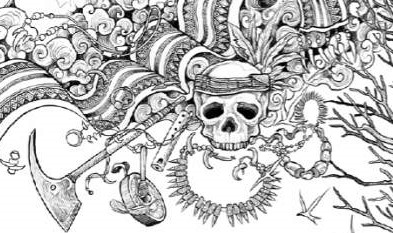

Step inside the house of the title; don’t be alarmed by the fence of human bones, and don’t stop to wonder if this house was even standing here yesterday. Yes, those are great big chicken legs curled up underneath it, and perhaps the house is flexing on them somewhat, poised to move or even defend itself if you prove other than what you seem. A fire is burning, food is cooking on the stove, and a cup of kvass is waiting for you. A mysterious door in the corner of the room remains temptingly shut, but that is for after you have feasted, told your host about your life, and heard a little of hers.

Her name is Baba Yaga. Perhaps you know it already: perhaps you rode with a brave young Prince, in another story, begging for a magic talisman from Yaga to help you track down the fabulous Firebird and win the hand of a princess; or perhaps you arrived by accident at this strange house and helped her daughter to escape, and then were hunted by the witch in her flying mortar, shuddering at every gnash of her great iron teeth. There are many stories told about Baba Yaga, within and beyond the canon of Russian fairy tale.

I have a vague memory of encountering her as a small child, in a picture book of the Firebird? I expect I was inclined towards her because I called Mum’s Mum ‘Baba’ – she disdained ‘Grandma’ because it made her feel old (none of us knew we were using the same name from another culture) – but I found her frightening too. I loved witch-stories from an early age, and I must have responded to Baba Yaga’s unpredictable character: no Glinda the Good Witch, her. She’d help you or devour you on your individual merit. Plenty of ink has been spilled on trying to interpret Yaga’s origins: did she embody a storm cloud, a matriarchal goddess, a lunar goddess, a memory of Persephone?

Whatever her origins, she continues to have a long and varied life. Sophie Anderson’s interpretation – the grandmotherly old woman dishing up steaming shchi from a huge black pot – is faithful both to Yaga’s associations with the dead and her long history of reinventions. This Yaga is a psychopomp (I’ve always loved that word, and get to use it so rarely), guiding the spirits of the dead into the next world. Her house has legs because it covers so much ground, visiting remote corners, where the smell of festive cooking draws ghosts from far and near. Perhaps you hadn’t realised that, seated at this nice table, enjoying the earthly things of the world: you’re being readied for whatever lies behind that door.

But perhaps you’ve spotted someone else in the house on chicken legs, a girl watching you from the periphery of the scene. Marinka, Baba Yaga’s granddaughter, with a sombre expression. She has never known her parents, only this house and Yaga, and she really should be involving herself more in this process, listening to the specific words, learning the language of the dead, because one day – perhaps sooner than she expects – Marinka will be taking on this role.

But that is there is a problem, one that drives this wonderful novel, pushing its characters to do daring, huge, tiny, impossible, stupid, wonderful, treacherous, human and magical things: Marinka doesn’t want to live this life. She wants to live among people and have friends who are not just spirits on the brink of something else. One day, her Baba will go through the gateway into the land of the dead herself, and Marinka will fully inherit the identity, the history and the responsibility of the Yaga. But if Marinka has her way, she won’t.

Without risking spoilers, it’s worth saying how refreshing it is to see a children’s fantasy novel without a villain. Certain genres and conventions seem unavoidable after a while, and the assumption is often that younger readers demand constant peril and clean moral distinctions. This novel is about a girl whose compass is spinning from the very first page, and we are with her, wishing for some form of escape. We long for her to find a friend or have an adventure that will in some way resolve her anxiety about the future – but every action has a consequence, and this isn’t a story about tidy options. It’s driven by emotion, fuelled by secrets, and its route is unpredictable and bumpy.

The narrative flies along, and Anderson keeps us guessing, but this is also a novel of subtlety, of a sort only a fantasy novel can achieve. When Marinka’s house brings her to a new city, for example, and Marinka throws away her headscarf because it makes her look like a Yaga, or when Marinka agrees to a ritual of formal inheritance while a secret betrayal burns darkly in her heart, complex ideas of cultural difference are being invoked. What might initially appear an adventure about escaeing from a hard life, perhaps with some spooky, Tim Burtonish furnishings, quickly becomes a novel about precisely those details and their authenticity: about how folk and fairy tales like those of Baba Yaga help us grapple with the impossible aspects of the world. It is also about how these tales are an inheritance available to all of us: the House is waiting for you or I to enter, sit down and share our stories.

Though it carries its character into extraordinary circumstances, their emotional truth is richer for that kernel of folkloric strangeness. Anderson gives the folk tale a cultural authenticity, never simply adopting it for an exotic flavour, whilst also playing about with it making it structurally, even societally meaningful (a whole Yaga culture, with its own rules, stories and newsletters) within Marinka’s world. It’s a deft achievement.

I first read this when it was Book of the Month at Waterstones (in fact, it was launched in our store –three men in red silk shirts playing balalaikas in the history department: it was great). After that it was on the shortlist of the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize, and now it has joined the Carnegie Shortlist (alongside, peculiarly, a number of other children’s novels about grief and death). It deserves all this and a long life too. Not only that, I can’t wait to read what Sophie Anderson writes next.